I. Talking Gun Safety in Clinic

By Chris Moellering, MD

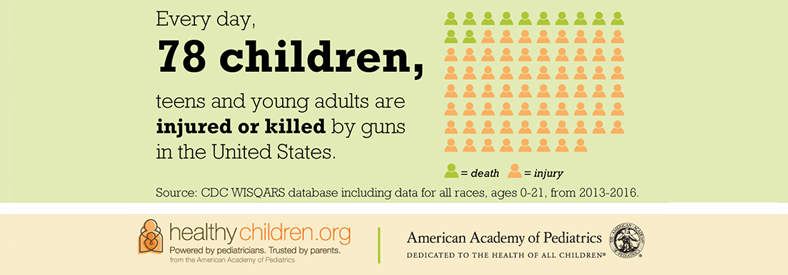

Many topics have become polarized in our current political climate and gun safety is no exception. The topic has become so taboo many individuals avoid it completely. However, there are facts about gun violence that cannot be denied. Gun violence affects children; children who witness gun violence on the streets; children of individuals who take their own life with a firearm; adolescents who take their own life; children who are killed when they are caught in the crossfire of violence on the streets, or when they become accidental victims when firearms are not stored safely in the home. In fact, firearm injury is now the third leading cause of death in children ages 1-17 and lags behind only motor vehicle accidents in injury-related death.

But while many pediatricians feel comfortable talking to their patients and families about car seats, seat belt safety, and the dangers of texting and driving, broaching the topic of gun safety can be very uncomfortable. Research, however, shows that most patient families are receptive to what their providers have to say about gun safety. A study published in Pediatrics in 2016 asked individuals, including gun owners, if they thought that pediatricians should talk about safe storage of firearms. The results showed that 75% of individuals surveyed, including 71% of gun owners, thought that pediatricians should talk about safe firearm storage. The pediatrician’s office is a place where families go to talk about how to keep their child safe and healthy, whether it be by learning about proper nutrition and healthy habits, or by preventing terrible tragedies like SIDS, drownings, head injuries, poisoning, and choking. If I can tell a family they need to anchor their televisions to the wall to prevent them from toppling over, or to make sure laundry detergent pods are out of reach and inaccessible, it should not be a stretch to tell them to keep a firearm unloaded and locked.

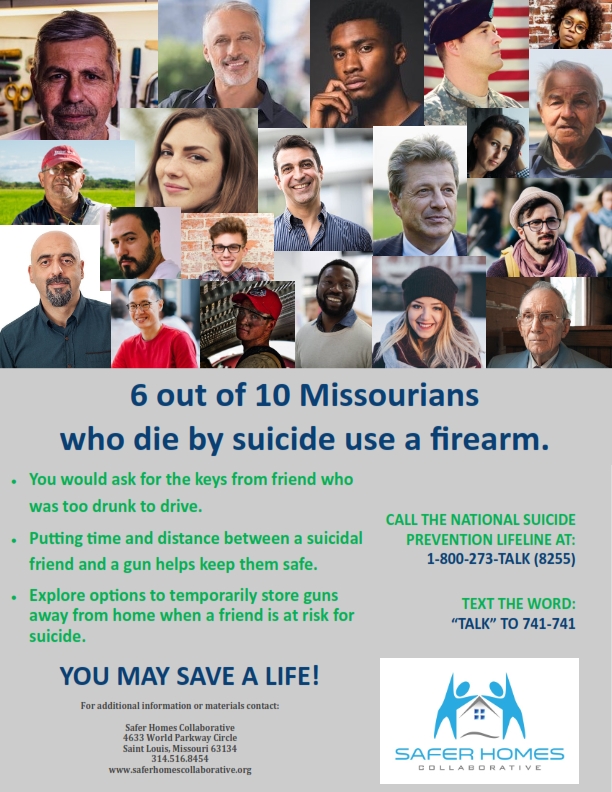

A harder conversation, however, can be talking to the family of a troubled adolescent about the dangers of suicide by firearm. That being said it is perhaps the most important conversation to have. According to the CDC suicide is the second leading cause of death in individuals between the ages of 10-34. Not only that but the rate of suicide increased by 28% from 1999 to 2016. When you add to that the fact that 60% of suicide deaths are due to firearms, it becomes a topic that cannot be avoided.

MOAAP has created a work group to address gun safety that is open to all members. Our goals are three fold: 1) increase provider comfort level with educating regarding gun safety 2) spreading information within the community about firearm safe storage and suicide prevention and 3) promoting gun safety at the state legislative level. Look for more resources coming from this committee in the near future to help you have the conversations in your practice that will help keep your patients safe and protect them from firearms injury.

II. Suicide Prevention Guidance

III. Screening Recommendations for Practitioners

“Pediatricians and other child health care professionals are urged to counsel parents about the dangers of allowing children and adolescents to have access to guns inside and outside the home. The AAP recommends that pediatricians incorporate questions about the presence and availability of firearms into their patient history taking and urge parents who possess guns to prevent access to these guns by children. Safer storage of guns reduces injuries, and physician counseling linked with distribution of cable locks appear to increase safer storage. Nevertheless, the safest home for a child or adolescent is one without firearms.

The presence of guns in the home increases the risk of lethal suicidal acts among adolescents. Health care professionals should counsel the parents of all adolescents to remove guns from the home or restrict access to them. This advice should be reiterated and reinforced for patients with mood disorders, substance abuse problems (including alcohol), or a history of suicide attempts.”

IV. AAP Policy Statements